Forging Family for Those in the Margins

Posted by: DVULI | August 29, 2022

by Kimberlee Mitchell, Staff

► Myron Bernard hopes to close the homeless gap among urban youth.

To see Myron Bernard (Seattle/Tacoma 2011) speak or lead a training session is impressive. His resume is equally as telling. One would never assume that his career choice of serving youth pushed out to the margin is rooted in his own childhood trauma.

To see Myron Bernard (Seattle/Tacoma 2011) speak or lead a training session is impressive. His resume is equally as telling. One would never assume that his career choice of serving youth pushed out to the margin is rooted in his own childhood trauma.

The second son of first-generation Korean immigrants, Myron’s parents met and married in Korea. Prior to their union, however, his mother was subjected to fundamental abuse. She was sex trafficked as a child, which led to significant trauma. After his parents moved to the US, Myron’s mother was hospitalized to treat schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and depression during his formative years.

“While I was in fourth through seventh grade, she remained in the hospital,” recalls Myron. “I didn’t have my mother. It wasn’t like she was trying to abandon us–the circumstances of her health didn’t allow her to be present.”

To keep a roof over their heads, Myron’s father had to work several jobs, which meant leaving his sons (born a year apart) home alone.

“My brother and I would go for a week or two without seeing an adult in our home,” Myron says. “We grew up, like a lot of children, wanting to be good kids; however, we didn’t have direction and we’re hungry, so we ended up at the mini-mart to steal a bag of Doritos for dinner.”

Myron and his older brother developed two distinct responses to their environment. Myron finished high school with a 4.1 GPA, whereas his brother graduated late after dropping out. “I was trying to earn love and make people love me,” divulges Myron. “And my brother was kind of giving two middle fingers to the whole thing.”

Myron and his older brother developed two distinct responses to their environment. Myron finished high school with a 4.1 GPA, whereas his brother graduated late after dropping out. “I was trying to earn love and make people love me,” divulges Myron. “And my brother was kind of giving two middle fingers to the whole thing.”

Myron struggled with his areas of trauma, abandonment, and family attachment issues and had to work through those things as an adult. “Later in life, as Jesus began to work on my heart, I found massive love for young people who did not experience God’s love in a family unit,” he explains of his healing journey. “That’s what really drew me into urban youth work. My heart always went out to young people who were pushed to the side.”

As a youth worker, Myron found himself serving young people who were contending with unstable or inadequate living arrangements. “There’s a difference between chronic homelessness and those who are transitionally or temporarily homeless,” explains Myron. “The vast majority of people experiencing homelessness are not in that chronic state. Some couch surf for years, bouncing from house to house.”

The broad spectrum of housing insecurity ranges from living on the streets or in a car to having a roof over your head but under the constant threat of being forced to leave. “Seeing eviction notices on the front door and wondering if you have a place to stay that night leads to significant trauma in the young person’s life,” says Myron, who was never homeless but moved often–living wherever his father could afford at the time.

The broad spectrum of housing insecurity ranges from living on the streets or in a car to having a roof over your head but under the constant threat of being forced to leave. “Seeing eviction notices on the front door and wondering if you have a place to stay that night leads to significant trauma in the young person’s life,” says Myron, who was never homeless but moved often–living wherever his father could afford at the time.

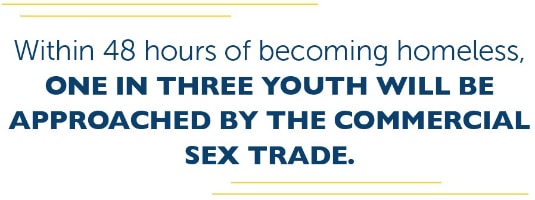

In Pierce County, Washington, where Myron works, 1 in 20 youth are homeless on any given day. Statistics show that if youth do not have consistent, safe housing (i.e., reunited with their families or given assistance to transition to independence), they become more vulnerable to being preyed upon. *In fact, within 48-hours of becoming homeless, one in three youth will be approached by the commercial sex trade.

“The biggest challenge is that the current system is not designed for young people who are in that space because youth are treated differently legally,” explains Myron of the system’s failure to properly protect and support minors. “They’re always asking what is going on with the parent.”

As Myron got more involved in youth ministry, he began to see firsthand how easy it was for youth to face homelessness. One summer, he had a poignant reality check when Youth for Christ (YFC) hosted an inner-city youth camp.

Two campers needed to leave camp urgently due to being evicted, and their mother needed help moving their belongings. In the car ride down the mountain, one of the sisters was overheard asking the question, “Is this dude Jesus going to give us a place to sleep tonight?” Her comment hit Myron hard. A “Jesus experience” at camp wasn’t their fundamental need. He identified this as a real-life correlation to Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs and concluded, “Unless there’s a foundation of some stability and safety in life, the ability to spiritually receive and process who Jesus is will not be possible.”

For youth workers, recognizing signs of homelessness in young people can be tricky because they all want to fit in. Inconsistent adequate hygiene is the most common sign, but youth can hide it well. Another sign is when youth direct you to meet them somewhere like a friend’s house when asking where to pick them up.

“When family and the emotional and physical support are removed from someone’s life, it’s easy for homelessness to become a reality,” explains Myron. Meaning there are a lot of complicated factors that lead to the experience of homelessness, especially chronic homelessness.

Myron believes urban youth workers have the unique opportunity to bridge that gap and be a connector. “We get to forge a new family around them when the nuclear family breaks down,” he says. “Forged family is the creation of resources and the strength around the youth’s life that God had intended the family to provide. God has always worked in tribes, collectives, and communities of people who surround, love, and care for each other. We get to help build and be part of that community as a forged family.”

When it comes to serving broken and marginalized youth, Myron insists you have to intentionally go to the borders just like Jesus. “It’s an encouragement for every youth worker and youth organization,” he charges. “There are kids in every city and community across America on the verge of tragedy and trauma. Jesus calls His church to protect those lives. They’re not going to necessarily come to us. We have to meet them where they are.”

This article was published in the Summer 2022 issue of DVULI’s On the LEVEL print newsletter.